This post is part 2 of a series. Read the previous part here.

Songs My Manager Taught Me

Last time, we discussed entropy and looked at PlayPumps, a charitable initiative that failed due to its backers believing in an unrealistic narrative and lacking a real understanding of the world.

In this part, we'll talk more about narratives in action.

It might seem like I am extremely opposed to the use of narratives in decision-making, but I am not. Narratives are tools, and I learned how to deploy them in my job, under the tutelage of a chief engineer in my organisation.

He mentored me in my first year - in fact he was my manager. I was tasked with preparing drafts of all kinds of documents - memos for strategy changes and updates to procedures and standards and things in that vein.

When reviewing my work, he would always ask: "what's the story here?"

I used to think that technical writing had to consist of statistics and facts only, no bias. He painstakingly corrected this tendency. Narrative is important, because it provides context for all the facts. No one is interested in free-floating facts. I could say that some risk is a 1 in 1000 years occurrence and has the potential to kill at most one person, and no one cares, until I embed the fact into a context.

Like so:

When we did this inspection last year, we discovered a 1 in 1000 year event with the potential to kill one person and cause an $8 million dollar financial impact. If we do nothing, this risk will become more likely. But here's another course of action we can try.... There's a few problems we need to resolve to get there, but we've already started to work on them. One of these steps involves you letting us spend $1,500,000 - could you help?

That is the story my manager would look for - the framing around raw data that would tell the reader whether a fact is good or bad. Value-neutral facts are by default not interesting. Being able to say if something is good or bad is important - and good or bad comes from a narrative.

Narratives are what gives information meaning. All information. It is how we understand and experience the world. Giving someone a spreadsheet of raw data is unlikely to build a useful shared understanding. Storytelling is the act of creating a shared mental reality with other people.

Hang on, though, we can always deliver these insights as mathematical or scientific models, can't we? If all my manager and coworkers need to know is risk goes down when we do XYZ, then we should just go with models, right?

I would argue no. Absolutely not. Models are for cowards who are checked out and can no longer tell whether facts are good or bad. What differentiates a story from a model is the presence of emotion - the only reason why you'd give a shit about any of it.

I don't know the thickness of a lot of equipment I dealt with off the top of my head. I do feel the tangible twist in my gut when I see that it is a fifth as thick as it should have been - because every day, many inspectors and operators and mech labourers and engineers walk up to this pipe, and when it's lost so much steel, my pipe is one slug or unusual pressure surge away from exploding, and so the 80% wall loss is not a value neutral fact.

The diminished thickness of that pipe is a bad fact. A scary, keeps-me-up-at-night fact. It is a fact imbued with emotion, and because I have this core emotion, the story, the narrative, is how I convey my dread and terror to someone who is in a position to do something.

I get creative with it, and you should too. Don't rely too much on words and numbers. Some of the best stories I've told were work emails where the punchline was photos of the corrosion damage, or videos of leaks, to imply "and then, this is going to explode and kill someone, we're going to make the news, and we're all going to lose our jobs."1

To do this well, you really need to genuinely care - because emotions come out of values. Not the shitty top-down corporate values that the empty suits go around claiming that they hold, but true, closely held values.

A good engineering workplace should be full of stories. Every case study is a story. Many of the most important stories aren't written down, and you'll hear about it when your bosses' boss is five beers in, and it'll be about the time, decades ago, when they went toe-to-toe with senior management to delay startup of a widely-hyped project because at the last moment, they discovered that the contractors has put socks and underwear under the cladding instead of thermal insulation because they hadn't ordered enough, just to avoid the penalties from missing the deadlines.2

Stories and narratives don't just determine how we understand the world, but also what we ought to do and what we should care about. The anecdote about the engineering team who fought with executives and won establishes that it's the right thing to do to protect the plant from short-sighted decisions - not just because it would have been more expensive further down the line, but because we care about the plant not exploding and killing our coworkers and friends and ourselves.

I worked with some other people who have loads of stories from when the engineers lost this same fight, and the result was that people were killed, the facility being permanently decommissioned, and everyone being laid off. This is also important, especially for an early career engineer, because it gets everyone to align on stakes. This is what success looks like. This is what failure means. This is purely imaginary, while this other scenario is real and has happened before.

Per Doc Burford on writing stories and scripts:

Stories are, in other words, a necessary component of the human animal’s ability to function in a healthy way. Take an animal that is predominantly emotion-driven (if we weren’t, then when presented with facts that contradict previously held beliefs, we would have zero trouble altering our beliefs — as you know, that doesn’t happen… because humans are emotional animals!), give it some roughage to help it digest its real experiences, and bam, you have a healthy human being. Stories are a necessary component of this process.

I'd argue that organisations, which are made of people, also need stories, and my first manager did a lot to help me understand that even though my job title says engineer, my real job is to contribute to the organisation's narrative - its lore and identity - to keep it moral, factual, and relevant. I do this by aligning to the Way Things Are Done Here, aka our local culture, which I absorb via stories - about what other engineers did, or didn't do - because I need those stories to inform myself of facts and values and identity.

"What am I doing here?" is a question that can only be answered by the prevailing narrative in any given workplace. Culture, the intangible fabric of what people will do at work, is stored in the narrative.

These cultures / narratives can rapidly become harmful when they stray from being moral (such as with Enron exploiting the electricity market to enormous profit, at the cost of all the consumers) or factual (such as within the Russian military).

We'll now look at what a dangerously irrelevant narrative can look like, illustrated using the events of September 2010, at Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E).

Seeing Like the Director of Integrity Management

Here is a case study from the 2015 book Nightmare Pipeline Failures: Fantasy Planning, Black Swans and Integrity Management by Jan Hayes and Andrew Hopkins.3

On the 9th September 2010, just after 6PM, a large fire / explosion suddenly erupted4 in San Bruno, a SF Bay Area suburb next to the airport. The cause was the rupture of a buried gas line owned by California energy utility Pacific Gas and Electric, or PG&E.

A root cause investigation identified that:

- The ruptured line was constructed in 1956

- It had ruptured along a defective longitudinal seam weld, which seems to have been a fabrication defect that had been there from day one

- There was no evidence that this section had ever been tested or inspected - not when it was first built, not at any point during 50 years of operation

So, what was PG&E doing? Why didn't they know about this flaw, and why didn't they inspect this line?

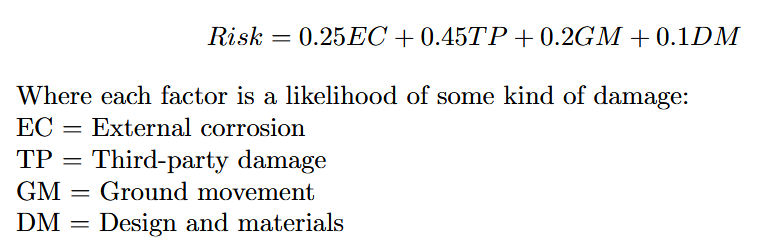

The company had an integrity management program, which started out by dividing the overall pipeline system into pipeline segments. Each segment was assigned a risk score, which was calculated based on four factors. Each of these four factors was given a weight, and then added together. Specifically:

So, each pipeline segment gets a risk score, and PG&E would select the highest scoring segments for inspection and maintenance.

Savvy readers have hopefully already noticed a major problem with this method - this formula averages out risks, making it impossible to tell what the true, absolute failure probability would be. Consider these two hypothetical scenarios -

Scenario 1: 40% EC, 30% TP, 20% GM, 30% DM; the PG&E risk score would be 30.5

Scenario 2: 90% EC, 10% TP, 10% GM, 10% DM; the PG&E risk score would be 30

Without using a calculator, it should be pretty clear that the absolute failure probability of Scenario 2 is over 90%, because the EC factor already has a 90% probability of failure and there's no way to argue that the other factors reduce that risk because that is just not how probabilities work.5 The weightings on each factor are a distraction - they're not relevant at all.6

This risk index score is worse than just listing out probabilities for each of the four factors individually. I bet it's actually worse than guessing based on vibes. At least then, you can look at something fairly rusty and go, "wow, that looks pretty bad", and go with your gut - the risk index score actively works against someone trying to get a good idea of risk in the pipeline system. A risk score of 30 means absolutely jack shit here because it fails to distinguish between something that's at basically imminent failure from one factor, vs something where every factor has a modest but not massive risk.

This process would never have produced a meaningful understanding of risk anyway, but wait, there's more!

It turns out that even if they'd used a risk assessment and ranking process that didn't suck, they still wouldn't have understood their pipeline risk, because all the inputs came from the company's GIS system which was found to be riddled with errors! Per the CPUC investigation report:

Data Management – It was extensively reported PG&E’s first submission of incident data to the NTSB included information that incorrectly characterized fundamental aspects of Line 132. Based on discussions with PG&E staff, experienced piping engineers were well aware the San Bruno segment was double-submerged arc welded (DSAW), rather than seamless. However, it is not clear whether the process by which data was collected and examined for threat identification and the risk ranking of piping segments (which should include examination of construction and operating records by those experienced piping engineers) has been consistently undertaken

The comment that experienced piping engineers being well aware about the weld is due to the size of the line. This was a 30" diameter steel pipe, which are too big to produce seamless - those cap out at around 20" diameter.

While we understand the entire pipeline industry has had challenges in digitizing and systematizing all the engineering design, construction and operating data, we find PG&E’s efforts inchoate. The lack of an overarching effort to centralize diffuse sources of data hinders the collection, quality assurance and analysis of data to characterize threats to pipelines as well as to assess the risk posed by the threats on the likelihood of a pipeline’s failure and consequences.

I did my own digging (NTSB docket, Exhibit 200, page 28) and it looked like the data was managed by a "mapping team". There was a digitisation effort in the late 90s, which converted hardcopy documents into a new digital system (the GIS). This did not seem to be subject to adequate quality assurance. .

Subsequent corrections (the PG&E employee suggested there were a lot) would be made by field personnel who would lodge a form to mapping, which apparently "have procedures and processes they follow". Transcript of an interview with a PG&E employee:

A. They would go out research where the job is located and check out the job from the local office that it's stored at.

Q. So would they physically go to the excavation location and find out that the bump or pipe or whatever component may be, indeed is different than --

A. No, mapping does not do field checks

Bolded for emphasis: mapping does not do field checks.

I am sympathetic the fact that you can't go and dig up every single thing you find, and there's probably large distances involved so checking everything is likely impractical. But the PG&E employee didn't say, "we'll try to get physical evidence to update the map whenever we can, but it's not always practical."

No, the specific statements were that mapping has a procedure to update the GIS, and they follow it to the letter. No opinion was aired on the effectiveness of this approach. It just wasn't the job of mapping to do field checks or even try to - surely it wouldn't be that hard to contract out the job of checking physical infrastructure?

The GIS was how the organisation knows what physical objects it has to manage, and the entity tasked with managing GIS data had a clear policy of not doing field checks.

It's not surprising that the map is useless when those in charge of mapping explicitly deny even the mere possibility of laying eyes on the territory!

This integrity management process is a very elaborate way to spend a lot of time producing nothing of real value. This is the final boss form of Garbage In Garbage Out - where garbage enters a machine for churning even correct information into misleading and inaccurate slush, and the result is a spreadsheet that has no relationship with reality or whatsoever.

This system is offensive. It is offensive because it's clear, from the way nothing makes sense, and all the data is wrong in glaringly obvious ways, that no one actually really cared about the purported end goals - of making sure the piping isn't going to explode.

So why do this shit? Why hire all those people and waste their limited time alive, creating a worthless database and an even more worthless spreadsheet?

To prop up a story, of course! It all comes back to narratives in the end.

Specifically, this is all a story being told by one specific man - the PG&E Gas Engineering Director of Integrity Management and Technical Support. These snippets are from Exhibit 201 of the NTSB accident docket. Behold, a master storyteller at work!

So, as I mentioned earlier, Subpart O requires us to calculate the risk of all our segments. And I think -- I'm going off memory, but I think there's 40,000 [sic - 20,000] transmission segments and somewhere to that, plus or minus, in GIS.

So we run the calculation, evaluate it. We actually started risk management in '99, prior to Subpart O.

We put -- using that analog equation, we put number values on them. They're relative risk values they're not probabilistic. It's more about this pipe looks worse than this other pipe which looks better than the other pipe, but not as bad as the first pipe type of concept.

So we have -- and we can provide kind of general graph of how many segments we had in which level of risk priority. So we had taken -- for high risk, for example, I believe that it's the number of 1,950 to 3,500 ... we have a graph that we can produce that shows what it looked like in 2001 and what it looks like in 2009, after a series of mitigation. Not just integrity management mitigation, but we have what we call the risk management program,, which we take from that list as we continue to drive down risk, because of all of the mitigation we perform on it through DA and ILI7.

Yes. This is basically verbatim from the transcript. Our guy here is actually bragging about that same terrible risk assessment equation that we've just established does not work. To a room full of state and federal investigators who are, right this second, questioning him about his pipeline that exploded, killing 8 people and injuring more than 50.

The fact that the pipeline exploded should have shown that all their risk management efforts for the past ten years were futile and pointless, but old mate is still happy to sit there and brag about making Risk Number Go Down because somehow, he is still trying to say that the Risk Number is more important than the catastrophic tragedy that happened.

In fact, he's still got more to say!

We drive that down through a program we call Risk Management Top 100. That's an annual capital investment in some portion of the top 100 highest risk pipelines.

And that calls for -- sometimes that calls for replacement. Sometimes that calls for doing... survey or evaluation to get ore information about just how accurate that risk calculation is. That helps drive down the risk of the pipeline.

So we are -- because it is a deterministic or relativistic methodology, and because you have a continuous integrity management program after you get done with the survey, you're required to come back at least seven years later and do it again. You are effectively driving the risk to zero, because you will continuously drive this.

So what may have been... in 2001 the top 100 ran from 3200 points to 3500 points... you look at the top 100 today and it will be far lower than that.

So between integrity management and between this Risk Management Top 100 program, we have consistently driven the risk of the pipelines down year over year and we can show you graphical form, if you like.

What in the goddamn hell is he talking about? This deterministic or relativistic methodology is going to drive the risk to zero because they come back every seven years? I guess the steel will just politely stop corroding in the years after they do "risk mitigation"?

Also what the fuck does 3200 points of risk even mean? It's a relative rank, he's literally explained that a couple paragraphs ago - what's the point of reducing the absolute value of a relative score?

This is the missing link that explains what the integrity management team is doing, which cannot be described as integrity management.

In the book, the authors describe this practice as "fantasy planning" - take a physical system, create a representation of it on paper or in your computer database8, then get people to manage the map and demonstrate a risk reduction while the maintenance cost goes down. Maintenance costs will of course go down, because when you're doing fantasy planning, your risk reduction is only limited by your imagination, and with executive bonuses on the line, people are incentivised to get very creative indeed.

This isn't risk management. This is creative writing. These are the damned lies manufactured by abuse of statistics. The story they are telling is completely irrelevant to reality, and it is all, very clearly, being driven by our Director of Risk Number Go Down.

There were many interviews conducted by NTSB, with members of the engineering team. With the exception of Mr. Risk Management Top 100 here, PG&E personnel tended to answer investigators' questions with short answers, referencing procedures, saying "I don't know - it's not my job. That's not in the procedure", and similar things.

The network of procedures, rules, and protocols, and the 'objective' risk index scoring system form what Dan Davies calls accountability sinks.

A characteristically modern form of social interaction, familiar from the rail and air travel industries, has become ubiquitous with the development of the call centre. Someone - an airline gate attendant, for example - tells you some bad news; perhaps you've been bumped from the flight in favour of someone with more frequent flyer points. You start to complain and point out how much you paid for your ticket, but you're brought up short by the undeniable fact that the gate attendant can't do anything about it. You ask to speak to someone who can do something about it, but you're told that's not company policy.

The unsettling thing about this conversation is that you progressively realise that the human being you are speaking to is only allowed to follow a set of processes and rules that pass on decisions made at a higher level of the corporate hierarchy. It's often a frustrating experience; you want to get angry, but you can't really blame the person you're talking to. Somehow, the airline has constructed a state of affairs where it can speak to you with the anonymous voice of an amorphous corporation, but you have to talk back to it as if it were a person like yourself. ... the managers who made the decisions to prioritise Gold Elite members are able to maximise shareholder value without any distractions from the consequences of their actions. They have constructed an accountability sink to absorb unwanted negative emotion.

This is what is happening here. Entropy has done what entropy was always going to do - eat away at the piping, corrode the metal - and the NTSB investigation cannot, in good conscience, blame the impotent underlings who cannot stray outside of their limited remits; at the same time this Director also clearly didn't know this pipe segment was on the verge of failure, because he doesn't have access to data that would have told him that.

Since he made all his decisions using outputs from Serious Quantitative Process, it's impossible to argue with him, because That's What the Data Says. It's Objective because it's got Numbers9, and you can go fuck yourself with your "engineering judgement" and "experience", fuzzy, personal things that you can't prove without the machinery of the organisation to convert observations about the real world into something that fits an accounting framework.

Data gathering is almost never a neutral activity; it takes place within a theoretical framework. And what this means is that if the system for gathering, classifying and tabulating the data was designed by people who had a particular model, then the data will most likely support that model. Everything which is part of the model will be well-verified, data-driven, empirically based and so on. Everything which isn’t part of the model will be handwavey, subjective, “hard to quantify” and other synonyms for “probably special pleading and made up”.

The risk ranking model at PG&E presents a ridiculous model of the piping system - a fantasy. Restricting intervention to the Top 100 implies that they think they will only ever have at most 100 segments at risk. Throwing away information about absolute risk implies that it's not important - that they thought the absolute risk would never be high enough to worry about. They had no way whatsoever to monitor absolute risk - despite the fact that it's a physical system, so piping won't exactly wait patiently in a queue for its chance to be repaired, before blowing up.

Complex systems are always on the edge of catastrophic failure. They can limp on for a while in this degraded state, so during this time, the Director goes around bragging about reducing maintenance spend while "managing the risk", giving presentations about how the team is Targeting Maintenance Objectively and Efficiently Driving Down Risk and Continuous Improvement10.

It's pretty obvious that the one and only trait qualifying someone to be the Director of Integrity Management is the ability to convincingly say "Dont worry kitten", like this:

When a pipeline segment blows up, it won't be because anyone is negligent or lazy or stupid. It wouldn't be anyone's fault specifically. Sometimes, these things just happen. We're very sorry, Regulator, Government, and Public - but we're as helpless as anyone.

This is what happens in an organisation where engineers do not have an independent identity. They do not tell stories where engineers make a real difference to public safety. There are no tales about disobeying written procedure or asking what the actual fuck is the Engineering Director smoking - or if there are any, they are purely cautionary tales, where the engineer in question quit or lost their job and then fell behind on their student loan payments and got eaten by the metaphorical or literal sharks unleashed by the creditors.

When this goes on for long enough, and junior engineers have no principled mentors left to learn from, they will instead develop this narrative:

You tell yourself that you're too stupid to understand what the Director is doing, that they're operating at a high enough level that bringing the risk index number down from 3000 is obviously the right thing to do, even though you don't really get it yourself.

You convince yourself of the wisdom of the org chart. You're just a lowly engineer, just out of college, you have an absurd amount of student debt - so you follow the procedures. Mapping doesn't do field work - and you don't want to think any of your coworkers are negligent or stupid - so you either give it as little thought as possible and avoid the cognitive dissonance, or you tell yourself that you're missing part of the big picture and that surely whatever you're doing makes sense to someone who's above you in some way - they're more experienced, more intelligent, more wise - which must be why they make more money than you.

For now, you keep your head down and learn, and your paycheck goes to paying rent and all those loans you took out to get here.

I'm convinced, even though I have no evidence, that this is partly why imposter syndrome is so rampant these days. In a world where huge organisations control and manage basically everything important for modern life - power, food, water, logistics, education - it is fucking terrifying to consider the possibility that the people on top are wildly incompetent. This means that at any moment, you are not safe - your plane could crash. The high pressure gas line under your home could explode. The highway bridge taking you home could collapse.

Either you're mistaken, or everything around you is broken. One of these options makes you hate yourself, sure, but the other one makes you want to crawl into a naturally occuring hole cowering away from any kind of infrastructure because all of these organisations are fucking it up, all the damn time.

But we cannot afford to keep ignoring entropy and dysfunction, because it's there, waiting, patiently, slowly driving our systems to breakdown. When things fail, people suffer - they get hurt, they get killed, they leave behind loved ones who will forever feel their absence.

People who lived in that suburb in San Bruno were going about their business one day when suddenly, a world of fire and pain. They were victims of PG&E's blatant disregard for entropic reality.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In Part 1, we discussed entropy and how stupid things happen when people ignore it in favour of a more convenient narrative. In Part 2, we looked at the role of narratives in organisations in more detail, and looked at fantasy planning - building a completely irrelevant narrative, as opposed to confronting reality, and the tragic consequences.

Part 3 will be about how modern society, and especially people with power, fail to cope with entropy - which to be fair, I find it really hard, too. I will describe my own personal philosophy to live within the entropic world.

-

Horror is about implication. When working in maintenance, on an underinvested asset, pretty much every story you tell becomes a horror story. ↩

-

They won, by the way. The plant is better for it - if they'd started up without proper thermal insulation it would have caused huge headaches down the line. ↩

-

Also see the NTSB accident investigation docket ↩

-

I found this video of the fire, to get a sense of how huge it would have been. Also watch the surveillance footage of shoppers nearby noticing the blast and panicking. ↩

-

the math is left as an exercise for the reader, but if you wanna check your method (or mine!), the numbers I got was 76% for Scenario 1 and 92% for Scenario 2. ↩

-

They were allegedly based on historic failure rates, it's unclear what they're doing in this equation, and also, even based on PG&E's actual data they're wrong. ↩

-

Direct Assessment and In-Line Inspection. Notice that these are inspection methods, and he's cleverly claimed them as a risk mitigation, because apparently the integrity management team has the kind of magic eyeballs that will repair pipes just by looking at them! No wonder they're paid so much! ↩

-

The trendy way to market this now is to call it a "digital twin". Watch them try to also staple an unnecessary AI application onto this digital twin product! ↩

-

If you want to keep your job, never mention that these numbers seem totally meaningless while management is in earshot ↩

-

The hand gestures to make when reciting this sentence is left as an exercise for the reader ↩