In part one in this series, we covered the implications of ever-increasing entropy - we use up available energy to generate Work, and dissipate heat as Waste - which means there are no free lunches in the universe we live in. However people like to believe that they are, because they're attracted to narratives promising easy things.

In part two, we discussed narratives in more detail. Narratives are an important part of the human experience because they inform culture - what we value and what we stand for. Narratives are constantly abused in various status games - and when this happens they can get dangerously detached from actual reality, with horrific consequences.

In this third and final part, I want to look at why we don't know how to deal with entropy. As you can likely tell from the strange title, this post will be a little different - no case studies of failed projects, just my personal thoughts about the forces that we are all subject to.

Both of the case studies in part one and part two are relatively recent. People, particularly the powerful, shielded from any and all consequences, no longer believe in entropy. They don't realise that it even exists - and yet there are corrosion allowances written into our engineering standards, there are quality control and testing procedures, and in the not so distant past, we managed to accomplish things that would be impossible if we didn't have the ability to reckon with entropy.

So, this particular cognitive impairment is a relatively recent one. What the hell happened?

Moloch Unleashed

Until the 1980s, things looked like they were getting better for humanity. We started out in primitive civilisations living crappy subsistence farming lifestyles, had a horrible interlude in the middle where some nations prospered off forcing less powerful nations to do the farming and production for them, and we had emerged into the 1980s. Postwar boomtime, waves of decolonisation, the Green Revolution, the Moon landing, and we eradicated smallpox. The Cold War ended.

We've made it to the end of history, humanity's happy ending when we're on track to solve every problem and end scarcity forever.

Forty years on, that conclusion looks a bit silly, but back in the day when victory was declared, it was thought that capitalist democracy was definitely the best system, so let's really double down on capitalism and unleash the power of the free market! Neoliberalism dominated the highest level of government, everywhere in the world.

Neoliberalism gave us shareholder theory - that the sole social responsibility of a business is to increase its profits. Nothing else mattered. The shareholder would take the money and then use it on whatever else they valued, and the more money you have, the more you can pursue your values, so the business was really doing the right thing by giving everyone as much money as possible.

Since we're reading this in 2025, we know how that went. Opiod epidemic. Subprime mortgage crisis. Widespread fraud. Abuse of workers.

Why it went so badly is a little more mysterious. After all, companies are staffed by people, and very few of us care about the share prices that much. How did neoliberalism convince us to go along with this ghastly machine?

In fact no one really seems to want to be doing this much damage to the world, and the mindless imperative to grow has been criticised extensively. There's an economic degrowth movement, lots and lots of protests, so my take isn't particularly novel. Economic growth is making many people, possibly even a majority, miserable - why do we all keep grinding on?

In the very excellent essay, Meditations on Moloch, I found my answer. It's Moloch.

The implicit question is – if everyone hates the current system, who perpetuates it? And Ginsberg answers: “Moloch”. It’s powerful not because it’s correct – nobody literally thinks an ancient Carthaginian demon causes everything – but because thinking of the system as an agent throws into relief the degree to which the system isn’t an agent.

Moloch is present in every system where participants all hate what they're doing and everyone ends up obviously worse off. It's the force driving the race to the bottom when there's no way to coordinate a stopping point.

There is no universal switch, no mechanism anyone can manipulate to say "okay, that's enough, we can stop growing now"1.

Within the perspective of a singular company, the share price must go up, because if its share price drops it will immediately get taken over by a bigger company or corporate raiders, or its rival will seize on its moment of weakness (less borrowing ability, etc) to drive it out of business.

The government isn't going to step in to stop economic growth - they can't! Economic growth is an arms race between nations over who gets to be in charge. Within a capitalist system, wealth equals control and creation - in fact control of the creation of resources. If the national economy slowed, the obvious next thing is that someone richer than you eats you alive. You end up with the entire productive capacity of your nation bought up by either American or Chinese firms and everyone being stuck in horrific factories and plantations producing goods and earnings for foreign investors, forever.

In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. The process continues until all other values that can be traded off have been – in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out a way to make things any worse.

Milton Friedman had not realised that he was summoning Moloch, but if it wasn't him, it probably would have been someone else.2 But even though we're all stuck in this horrible competitive system, we don't have to actively make it worse, right?

Neoliberalism provided the impetus to keep doing this. It really took off in the 80s, when groups of private equity firms would do leveraged buyouts on firms they believed could 'do better' - they took out debt, bought a company, then left the company to pay the debt. Initially, the business world did not like this, and fending off these raiders started taking up a lot of their attention.

There were only two avenues to avoid these wolves - take out debt yourself (but now you have creditors to deal with), or become bigger than them - increase your share price until they can't borrow enough to buy you. These options also suck, if you're concerned about running the business sustainably. Borrowing before the corporate raiders can means you end up with debt anyway, and relying on a high share price means that it must never ever drop. The profits must keep going up.

The actions of the corporate raiders were explicitly justified by shareholder theory and shareholder primacy, the idea that all society needs to be prosperous is for the line to keep going up, so don't worry about anything else - just make the line go up as fast as possible. If you fail at making the line go up, we will replace you with someone better, until we're growing as fast as we possibly can.

This idea is not a natural consequence of the system. It is promoted, constantly, by a class of people who are particularly good at making the lines go up. For this ability, within this neoliberal world, they are Moloch's favoured, and they have been granted awesome powers and titles beyond the ken of normal humans - like CEO, CFO, CTO, or venture capitalist.

They've been called various things - dunces, Business Idiots - but I call them the servants of Moloch.

They Broke Their Backs Lifting Moloch to Heaven

The servants of Moloch perfectly embody Homo Economicus - the rational, self-interested agent. They assume everyone else also serves Moloch and are utterly confused about valuing anything other than whatever thing they optimise for - usually money, sometimes titles or position.

They impart pearls of wisdom, such as:

-

Don't study that arts degree, you won't get a job. (Nevermind that you never know if the market will become oversupplied with STEM grads all following this same advice)

-

You should take that higher paying job over being a teacher. You always wanted to teach and you think you'll do a good job? But how will you afford to buy a home on a teacher's salary?

-

You should buy a home on a 5% deposit. Yes, pay the LMI and use your superannuation - if you don't buy now you'll be renting forever because everyone else is doing it!

-

You should lie on your resume - if you don't, you'll never get a job.

-

You should never swear or appear weird or do anything else to attract unnecessary attention

-

You should use ChatGPT so you can get your work done quicker. Consequences of inaccurate information? That's not for you to worry about, just get paid and promoted and someone else will deal with it.

Turning “satisfying customers” and “satisfying citizens” into the outputs of optimization processes was one of civilization’s greatest advances and the reason why capitalist democracies have so outperformed other systems. But if we have bound Moloch as our servant, the bonds are not very strong, and we sometimes find that the tasks he has done for us move to his advantage rather than ours.

You'd think that the winners of capitalism should all be brilliant ruthless optimisers, but the ability to game the system is not necessarily linked to personal capability or thoughtfulness. In fact, the slightest bit of introspection will reveal that the climb to the top is not remotely worth it.

This is because to serve Moloch, you can't really want or care about things. Moloch demands absolute fealty and you do that by throwing everything / everyone else under the bus.

It's so much easier to shove things into the fire if you have zero attachment to those things, so you avoid developing an understanding of why losing those things would be bad to start with. You can easily sacrifice things you do not understand - but if you do understand and become attached to things, you'll hesitate to make those calls and some Moloch-serving dunce will beat you in the competition. Hence:

The dunce, moreover, does not have the aesthetic sense to understand that what they've done is bad: they simply do not have the taste to distinguish good work from bad work.

Iris Meredith, Sam Altman is a Dunce

We're at the pointy end after forty years under leaders dedicated to worshipping Moloch - breaking their backs, demanding that everyone else also break their backs lifting Moloch to Heaven. Governments privatised vital public infrastructure, and capital let them rust away into uselessness. Social security was cut. They've thrown away things like 'workers dignity' and 'consumer protections' and 'creating things that work'.

As a result, the ideology trickled down to the common person, who is told to aspire to become a "girlboss" or engage in the "grindset" and to "lock in" and do whatever it takes within the bounds of what is legal. We're told that if you do all those things successfully, you will end up spending your days sipping martinis at beautiful beach resorts. If you fail to do those things, you'll be reduced to begging people for change at the bus stop.

It started from the top and is infecting much of the middle and the bottom. As we, as a society, have collectively decided to sell our souls to Moloch, we have created a truly shitty world.

We get Whatever goods and services. Make Whatever - the cheapest and laziest thing that would pass muster.

The MBA tendency to abstract away the operational parts of the companies they run - y'know, the parts that actually create the goods and services - that's Whatever. Whatever people wearing Whatever suits who run Whatever companies.

One former colleague of mine suggested3 that maybe the execs should just sell all the operational assets, stop putting money into the new developments, and buy Bitcoin instead, since management clearly does not want to deal with the realities of actually managing hazardous facilities. Cryptocurrency is great because it will allow them to get rid of the inconvenient traits of physical production plants such as exploding when you mismanage them, while still being a line that will go up and have dividends you can distribute to shareholders.

An aerospace company has lost the ability to build functioning planes. They didn't just lose plane-making skills by accident. These skills were sacrificed to the altar of Moloch, by executives who treat an aerospace company as a Whatever company. We make line go up by building $PRODUCT / providing $SERVICE (delete whichever does not apply).

Someone who engages with the world understands that no, I don't want to sacrifice being able to build this airplane properly for this stupid number to go up just a little faster. They will do the work methodically... and slowly. We can't have that.

The Moloch servitors will take note of whatever you're doing - because you're slowing down the growth of their Numbers! - and then you will be terminated. Another human sacrifice to Moloch!

Nothing But His Jawbone Remains

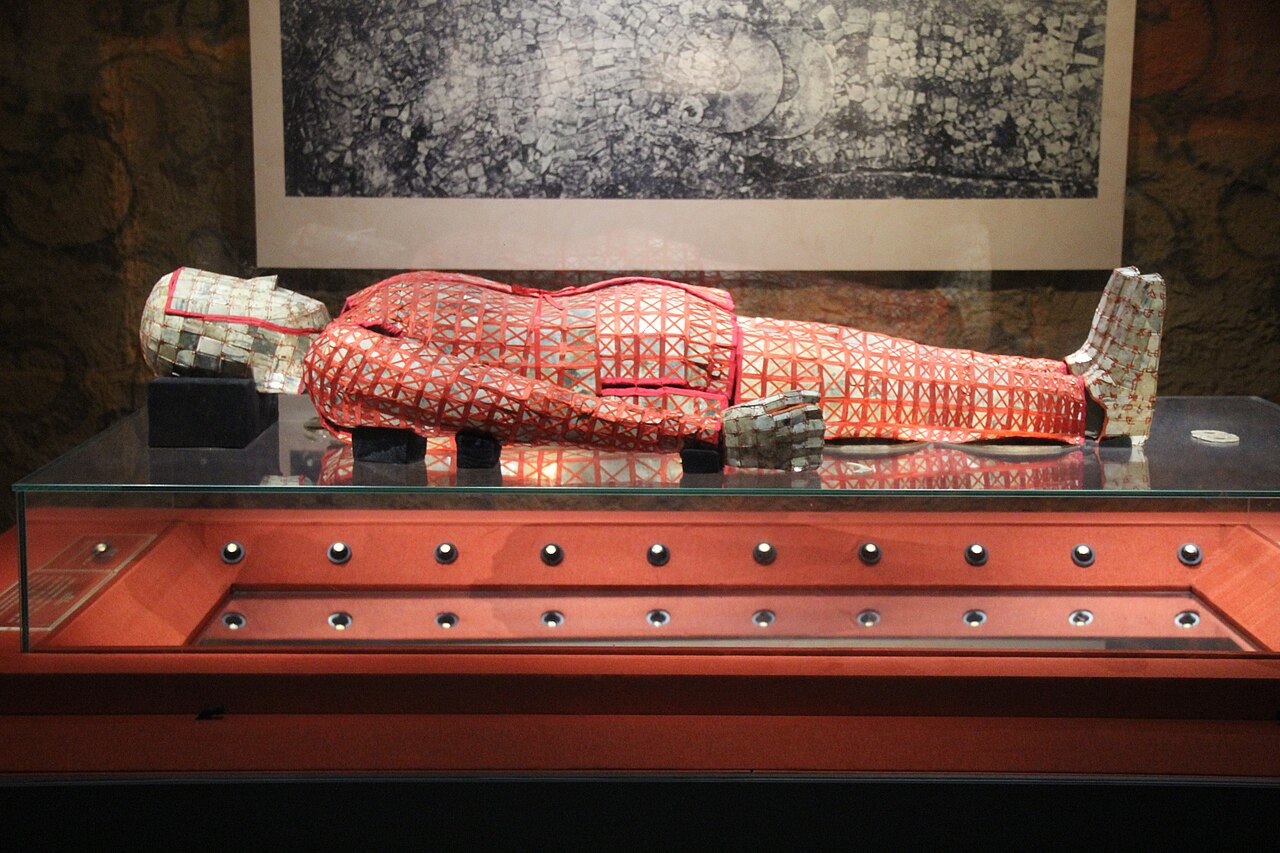

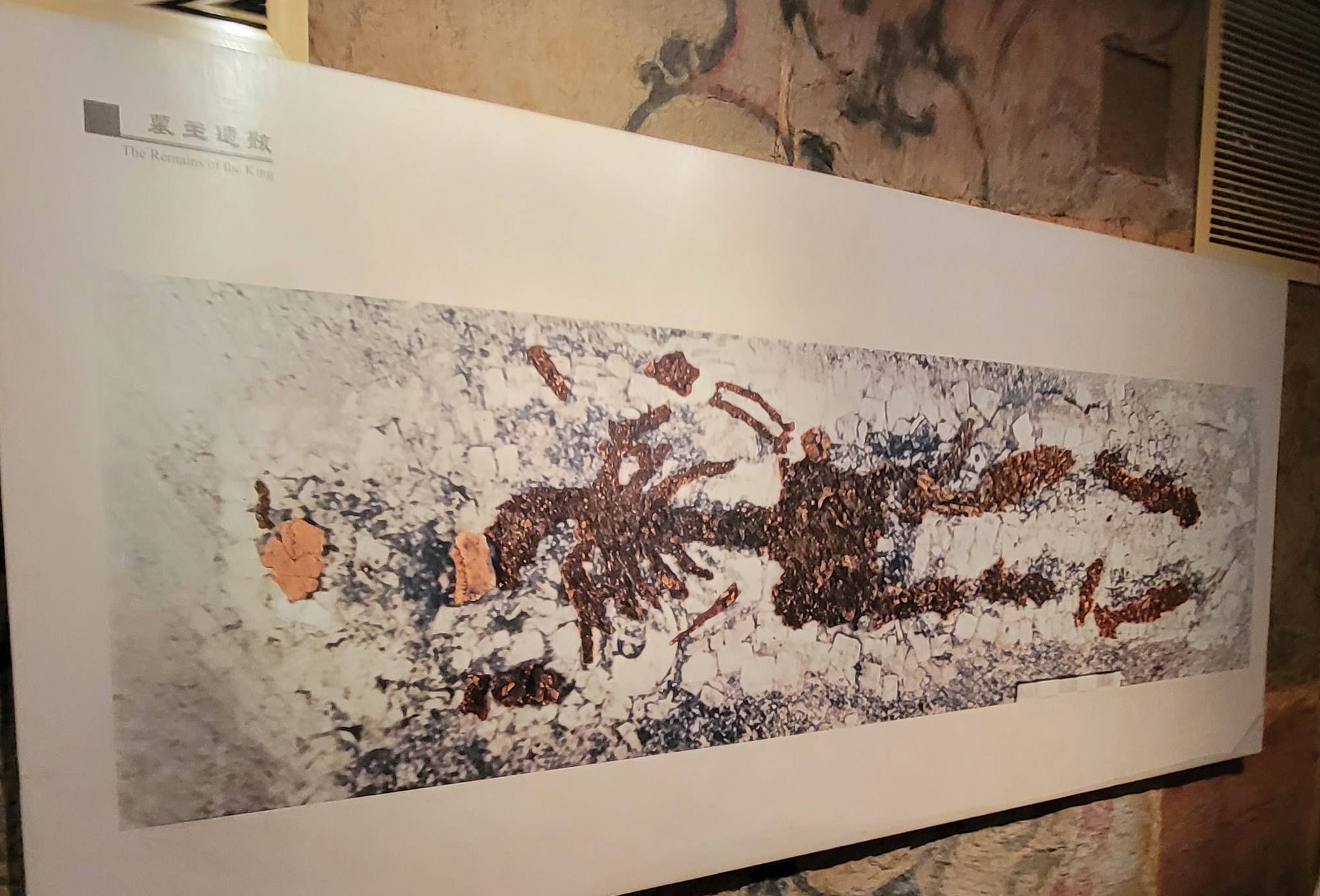

I spent some time recently travelling China, and I have visited at least four tombs / burial sites / necropolis of various ancient royals. This one really stuck by me in particular. It was the tomb of a king from around 120BC, unearthed when someone was building a hotel in the 80s.

This is not a mummy. This is a jade burial suit from about 120 BC - a kind of carapace made of pieces of jade, sewn with silk, cocooning the body of the dead king. They believed this would preserve his body and give him immortality. Needless to say this did not work - the construction crew found not a royal zombie, but some weird stains and a piece of his jawbone.

This is your eventual fate, jade suit or no jade suit, richest man in the world or homeless drug addict. No matter what your station in life was, no matter your wealth or power, the endgame is the same. Entropy will not be impressed with your resume, nor will it be disappointed if it is lackluster.

People who dedicate their life to serving Moloch cannot bear to reckon with death. Entropy is a reminder that nothing is permanent. No project you build is immune to the elements, no matter how much it costs. No achievement is eternal. You will die, and the sands of time will bury you - you and everything you have worked to create.

From Meditations on Moloch again:

“If you don’t work, you die.” Gotcha! If you do work, you also die! Everyone dies, unpredictably, at a time not of their own choosing, and all the virtue in the world does not save you.

“The wages of sin is Death.” Gotcha! The wages of everything is Death! This is a Communist universe, the amount you work makes no difference to your eventual reward. From each according to his ability, to each Death.

You break your back lifting Moloch to Heaven, and then Moloch turns on you and gobbles you up.

On the margin, compliance with the Gods of the Copybook Headings, Gnon, Cthulhu, whatever, may buy you slightly more time than the next guy. But then again, it might not. And in the long run, we’re all dead and our civilization has been destroyed by unspeakable alien monsters.

Nothing makes this understanding sink in as effectively as visiting the (incredibly elaborate) tombs of dead emperors. Regardless of their deeds, the people they have killed, the human sacrifices or their undoubtedly divinely ordained position in life - well, that's him now. A piece of jawbone in a glass case. Symbols of his authority - like his swords - were nothing but bundles of rust.

Entropy is a indifferent god that takes, takes, and takes.

A few years later, I read about Moloch, as seen through the eyes of the author, Scott Alexander:

I will now jump from boring game theory stuff to what might be the closest thing to a mystical experience I’ve ever had.

Like all good mystical experiences, it happened in Vegas. I was standing on top of one of their many tall buildings, looking down at the city below, all lit up in the dark. If you’ve never been to Vegas, it is really impressive. Skyscrapers and lights in every variety strange and beautiful all clustered together. And I had two thoughts, crystal clear:

It is glorious that we can create something like this.

It is shameful that we did.

Like, by what standard is building gigantic forty-story-high indoor replicas of Venice, Paris, Rome, Egypt, and Camelot side-by-side, filled with albino tigers, in the middle of the most inhospitable desert in North America, a remotely sane use of our civilization’s limited resources?

And it occurred to me that maybe there is no philosophy on Earth that would endorse the existence of Las Vegas. Even Objectivism, which is usually my go-to philosophy for justifying the excesses of capitalism, at least grounds it in the belief that capitalism improves people’s lives. Henry Ford was virtuous because he allowed lots of otherwise car-less people to obtain cars and so made them better off. What does Vegas do? Promise a bunch of shmucks free money and not give it to them.

Las Vegas doesn’t exist because of some decision to hedonically optimize civilization, it exists because of a quirk in dopaminergic reward circuits, plus the microstructure of an uneven regulatory environment, plus Schelling points. A rational central planner with a god’s-eye-view, contemplating these facts, might have thought “Hm, dopaminergic reward circuits have a quirk where certain tasks with slightly negative risk-benefit ratios get an emotional valence associated with slightly positive risk-benefit ratios, let’s see if we can educate people to beware of that.” People within the system, following the incentives created by these facts, think: “Let’s build a forty-story-high indoor replica of ancient Rome full of albino tigers in the middle of the desert, and so become slightly richer than people who didn’t!”

Just as the course of a river is latent in a terrain even before the first rain falls on it – so the existence of Caesar’s Palace was latent in neurobiology, economics, and regulatory regimes even before it existed. The entrepreneur who built it was just filling in the ghostly lines with real concrete.

So we have all this amazing technological and cognitive energy, the brilliance of the human species, wasted on reciting the lines written by poorly evolved cellular receptors and blind economics, like gods being ordered around by a moron.

Some people have mystical experiences and see God. There in Las Vegas, I saw Moloch.

Moloch complements my understanding of Entropy. Neither can be reasoned with. You could be the best orator in the world, but you can neither tell the stockmarket to stop optimising for growth, nor stop metal from corroding.

It's depressing to think about. Moloch is tearing our society apart and Entropy will take what remains, and we watch on, helpless to do anything. I felt doomed, like we were playing out the final act of a Greek tragedy and any time now, Poseidon would show up and drown us for our hubris.

Then I had a spiritual experience on the flight home.

The Shape of an Airplane

On my flight back to home, I got a window seat behind the wing. This is my favourite seat on an airplane because I get to stare at the wing, and think about what shapes the airplane. I'd been reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig, so I've been thinking about my time as a maintenance engineer, and the whole conceptual basis of maintenance in general.

That's all the motorcycle is, a system of concepts worked out in steel. [...] I've noticed that people who have never worked with steel have trouble seeing this - that the motorcycle is primarily a mental phenomenon. They associate metal with given shapes - pipes, rods, girders, tools, parts - all of them fixed and inviolable, and think of it as primarily physical. But a person who does machining or foundry work or forge work or welding sees 'steel' as having no shape at all. Steel can be any shape you want if you are skilled enough, and any shape but the one you want if you are not.

Just like a motorcycle, or the Las Vegas Strip, an airplane is a shape that already exists, before anyone even opens up any CAD program. It is a solution to laws of the universe - something that will fly given other conditions - and the engineer's task is to observe the laws of the universe and discover the functioning airplane.

This airplane has a precise shape that no one will ever create. That is the ideal airplane. Engineers then find the intersections between the ideal airplane and the parts we could conceivably manufacture. The edges of the ideal airplane are made a little more vague, so that there is a design tolerance - and this is the design envelope, which can be captured on a general arrangement drawing for manufacture.

Then after that, at the factory, the people who fabricate the plane will aim to stay within the tolerances, and the quality control people who inspect the parts will enforce the tolerances by rejecting anything out of spec.

This already involves dozens of humans per airplane part - which means hundreds, maybe thousands of people for the final airplane, but that's just the manufacture.

Afterward there is the maintenance. Once the plane is in service, inspectors check it at regular intervals to make sure it's still the right shape, to look for any indication that it won't stay that shape (such as fatigue cracks - many of which start out as hairline cracks, so thin that they are invisible to the naked eye). Entropy wears down our newborn airplane from the moment any of its individual parts are created, just like everything else. The act of airplane maintenance is to keep the shape of the airplane within the operating envelope.

The shape is a marvellous, complex contraption that flies - which people train for years to operate safely. In every plane there are at least two pilots (sometimes up to five) who have drilled, through study of theory, practice on simulators, and just plain doing the work, all the motions of safely flying an airplane, and a bunch of rare cases for emergencies.

I listened to the safety demo and watched the plane bank and the sunlight gleaming on the white wings (aerospace-grade coating on wrought tempered aluminium alloy - all specialised engineering products), the text on the window which I read backwards saying CRYSTALVUE COATED DO NOT POLISH, and I had a spiritual experience.

What happens when the airplane loses its shape? It ceases to be an airplane and becomes a big metal tube with pilots struggling with useless controls, full of scared people waiting to die.

It is important to understand that this is Entropy's outcome. The airplane is an aberration of low entropy and high embodied energy. Every time it flies, entropy increases, adding more fatigue cracks onto all the components. Entropy says, one day. One day you will fail.

The airplane-shaped plane is also not a value directly related to the share price, so Moloch has its eyes on it. A plane falling out of the sky is a tail risk that might only affect the share price on the day it happens. Moloch says through the voice of a manager or a superintendent, "If you won't sign off the airworthiness of this plane, I'll fire you and find an engineer who will".

Since I am home, writing this post, that didn't happen. We didn't crash.

In the shape of the Airbus A330, I saw another god - because it's not by my personal efforts that the plane remains airworthy and nor is it blind chance. There must be a third god - for only gods can oppose the action of gods.

This force, or god, is Care. Quality. Doing a good job, for the sake of doing the job well.

Care is the god that watches over you when you drive (it keeps the traffic signals working and ensures most people are following the laws). It's there for you when you turn the tap on at home (keeps the water flowing at the right pressure, and keeps the quality of the water at acceptable cleanliness and safety, with no nasties like arsenic or cholera or legionnaires), and when you unwrap some meat from the supermarket (the cold-chain logistics ensuring that at no point between the meatpacking plant and the supermarket, it had ever entered unsafe temperatures - and that every single pack you see is sealed tightly and thoroughly).

Care opposes both Entropy and Moloch.

It is how we beat entropy - day by agonising day. It is always a temporary victory. The dishes are washed - until next time. The bridge is painted - until the paint flakes off. The plane takes off and lands - this time. But while entropy is about inevitability, care is about today, and care ensures that today, we all live. We all get to cross an ocean in a few hours and then go home for a well-deserved sleep.

It is how we resist Moloch - again, one small fight at a time, pushing back on decisions which lack care. Sometimes we fail, and other times we win.

What makes it a god is that it lives in other people - who I cannot reasonably control or influence. Care is an action others must choose of their own volition. While Pirsig's idea of Quality is a personal relationship between a subject and an object - my god of Care is the nebulous net of other people's decisions and actions taken in service of their concept of Quality, which protects us from the indifferent alien gods - because Care / Quality are fundamentally distillations of human values.

Care may be a frequent victim of Moloch, but it can't really be the output of the optimisation process. It cannot be manufactured - only nurtured.

Safety - everyone getting to go home to their loved ones - cannot be achieved by blindly optimising for some Risk Metric in some Number Go Down process4. Safety is one of those Qualities, and to get me home safely, enough people valued this Quality to come together to make sure the airplane worked.

I wept. In a universe run by indifferent gods, there is one in our corner. The god of man-made miracles, a simple god of countless anonymous people who wake up every day and decide to do the right thing.

The Altar of Care

I am not a religious person, but I have found a god worthy of worship.

Care is the god of finally having enough to eat.5

Rice scientist, Yuan Longping, spent years hunting for a wild species of rice. He and his team grew hybrid rice by hand for ten years, defending it from farmers who wanted the grain now, avoiding the government's wrath for believing in politically incorrect science.

He refused to use bad, useless science, because bad, useless science doesn't grow rice, and people need rice to live.

He witnessed the Great Famine of 1959, and carried that tragedy with him for the rest of his life. His dogged pursuit for improved rice yields came from the fact that people need rice to live, not because rice is money - so he didn't commercialise his work. In fact, once China looked on track to grow enough rice, he donated his rice strains internationally. When he wrote about his work, he would couch the terms of yield gains not in dollar values, but in additional people the rice could feed.

These are the best and brightest champions of Care. Yuan Longping and Norman Borlaug, together developing rice and wheat varieties that feed the whole world; Jonas Salk and D A Henderson, inventor of the polio vaccine and eradicator of smallpox, respectively.

Let's compare what Moloch's best and brightest have created. Let's see, a shopping website (with warehouse conditions on par with 19th century factories). A way for every person to be hounded by targeted advertising throughout every corner of the internet, because fuck privacy. Apps specifically designed to make the users mad, filled with as many ads as possible. And of course, how could I forget:

A computer program that makes software development slower, writes mediocre content and tells lies.

Moloch has given us sparkling autocorrect and countless grifters desperate to win "innovation" awards.

Care took on Famine and Pestilence, two of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

PlayPumps and San Bruno both happened because they were careless projects. Care would have tested and verified the pump concept before installing any. Care would have checked the risk assessment methodology and verified the GIS data. Care would have stopped a non-viable charitable project in its tracks. Care would have prevented the pipelines from exploding.

These projects lacked care, because they were spearheaded by the servants of Moloch - when you've spent a few decades building temples, non-believers either leave in disgust, or are cast out. Servants of Moloch do not understand that failure fundamentally comes from not caring.

The same sorts of people involved in PlayPumps will be caught out by a different grifter. The same sorts of people involved in PG&E will fix their integrity management department but nothing else about the organisation, and then be surprised when the next crisis comes about.

Then when someone, somehow, feels the call of Care, and acts accordingly, they'll ask, "Why do you do this? It's like $GOAL with extra steps?"

I do it because I care. I don't mind the extra steps. Extra steps are the entire essence of what life is. Surviving without valuing anything at all is just dying with extra steps!

Care Through the Ages

Care extends past airplanes and roads and man's ability to generate electricity. Art and scholarship are enormous reservoirs of care, and I think, a really good way to show the timelessness of care.

We still sing songs from hundreds of years ago and preserve ancient paintings and continue to top up an ancient giant chalk figure.

In fact, that's the weird thing about care - that it doesn't die with its originator.

In my visits to the tombs, I formed the thought - care begets care.

Despite frantic attempts to avoid the spectre of death, all these emperors succumbed to Entropy. But their grave goods, in some cases, carried on.

Did you know that the famous Terracotta Warriors at the tomb of the first emperor of unified China was not found in its present state, of life-sized clay men, lined up in neat rows?

In fact, back in the 70s, when they first excavated the site, all the statues were found in pieces. Terracotta is a material that is prone to cracking, and entropy has done its work - that, plus numerous earthquakes over the eons.

The impressive army we see today - numbering thousands of clay men - had to be pieced back together by hand. Archeologists estimate that we've only restored a quarter of the figures. There is a restoration area behind the lines of statues for ongoing work, and behind it, an area still yet to be excavated - because at the moment there's no good way to preserve the original lacquer, but there's a university in Germany that's developing a method at the moment.

It sounds like an awful lot of effort for some statues, isn't it? But just look at them.

In the face of each statue, in every perfect detail, in the sheer numbers of statues which all have unique faces - we see the hand of Care. When we encounter and recognise care, very often, we find ourselves compelled to care, as well.

Someone, 2,000 years ago, sculpted a man with care, and then did it a hundred times more, and did it as part of a huge team. When we see something like this, we feel that we must preserve it. We invest additional time and effort to find out more about their creation, to piece the fragments of the statues and reassemble the army. The site is now a museum, receiving around 50,000 daily visitors on regular days and about 100,000 daily visitors at the peaks. The cynic may say that it's a glorified tourist attraction, but I reply - it can't be a tourist attraction if people don't care enough to turn up to this place by the tens of thousands every single day.

If something is Cared for, it will never truly die - not even if it lies buried for thousands of years. Not even if it burns down. It is not a sure thing - maybe we never would have found that tomb - but if we'd found a pile of random rocks in there instead, because creating statues and lining them up would be too much effort, we would have ignored it. We only care because we witness care.

Care is an obscure act - we'll never know any of those artisans who crafted those terracotta men, we have only their workshop stamps. Individual people, like the rice scientist, becoming known at all are rare. Care is not about being invited to speak on stages - usually the opposite. Usually it is toiling in obscurity, and letting the work speak for itself.

Care does not require a Great Man or a hero, in fact, usually quite the opposite. No large project can be successful through just one person caring, it has to be done as a team. Sometimes, unlikely teams exist in unlikely places.

This is why I consider Care to be a god, because it is a force that exists for as long as sapient people exist. In fact, caring is the hallmark of personhood. Animals do what is needed for survival, but I think the mark of personhood is the ability to sacrifice for some value orthogonal to survival or procreation.

Care transcends the barrier between people. When we care about a common cause, we light each other's torches, and carry on the work together. All thoughts of competition vanish. This is why working on teams that care feels absolutely electric, and working on teams that don't feels like a Sisyphean hell.

The flame of Care also transcends time, as we light torches in the present off a torchbearer who has come before us, who may be long dead but nevertheless touched someone with their caring. Entropy may try to extinguish the light, but through care, we can reverse its action on what we care about. We piece ancient fragments back together. We repair airplanes.

With Care, we fight entropy another day. Not a single one of us immortal, but perhaps all of us, in aggregate, we live on, protected by the grace of each other's care.

Worship at the altar of Care, and go forth and create Quality.

So, yes, I cry when I read this book, because it’s about what it means to be a grown-up. It’s about what it means to be human. Yes, you (really, you!) can go out into the cold and the dark. You can force entropy back just a little. You can make something great — and done in the service of greatness, even the small, careful, everyday things begin to glow with its reflected light. So what if the symphony turns back into black notes on a white page when you stop playing? God put you on this earth to create your own little pool of light and order, to take Nature’s form-giving fire for your own, to work not because it’s how you get paid but because it’s how you leave your mark. I’ve read a great many books lately about how we do that, but this picture book is one of the very few that gives the why. Beautifully.

Jane Psmith, Review of The Philharmonic Gets Dressed

-

Even a global pandemic barely put a dent in things. ↩

-

Chapter 8 of Dan Davies' The Unaccountability Machine gives a good discussion on Friedman ↩

-

Jokingly, I hope. ↩

-

See part two for a refresher on why ↩

-

There is also a parallel story for wheat yields - Norman Borlaug - but I eat more rice personally. ↩